Today is Jack Kerouac’s birthday. He would be ninety-two.

This might not mean anything to some people, but today is like a Name Day for me. While I’m definitely going to rhapsodize over how much his writing means to me, I’m also going to question every good feeling I have for him like I do every year.

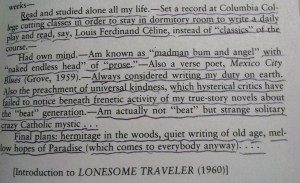

As I’ve previously mentioned, Kerouac was my gateway drug into literature. I inhaled him and kept him in my lungs, allowing his prose, poetry, and philosophy to seep into my bloodstream. I smoked a bag of Lipton tea in the boy’s bathroom in high school because I misunderstood his reference to pot as T, thinking he meant the drink and not THC. I drank sweet manhattans after reading about his attempt to save himself during his stay at Big Sur. The tears I wept at his melancholic and eternal October poetry were French Canadian tears. Every other book of his was either rolled up to fit in my back pocket as I took subways and ferries hither and yon, or revered and only read in my bedroom with wine and coffee far away from the white pages.

It’s disgusting, really.

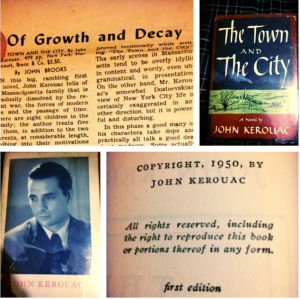

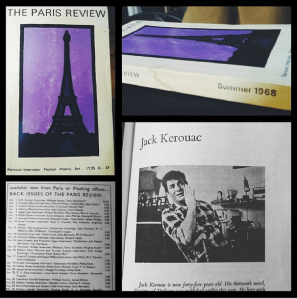

My girlfriend, Magie, bought me a first edition copy of The Town and the City, Kerouac’s first novel. The seller tossed in two newspaper clippings from the time of the release of the novel, including the John Brooks article from the Sunday Times, and Charles Poore’s from the New York Times. I was over the moon. I held in my hands a first edition copy of Kerouac’s first novel for the first time. I was scared to even breathe around it. I realized in that moment that I was now becoming a collector. Before I could make my first purchase, Magie found and gave me a first edition version of Vanity of Duluoz. Now that I knew I could acquire these gems, I scoured the internet for a back issue of the Summer 1968 edition of the Paris Review. It featured an interview with Kerouac in the twilight of his life, bloated, wrinkly, and red like a deflating balloon. When I finally found a copy on Amazon, I panicked.

“How could it only be $25?” I asked about the back issue.

“It’s just an old magazine,” Magie reminded me.

But it wasn’t. Although he never touched it, never saw it, and didn’t contribute anything to it, this magazine came out while Jack was still alive. It’s weird, though, because as most of his friends would probably say, Jack really wasn’t alive at that point. He was old before his time and he was confused. God, it’s just so sad.

But this is the part of my diatribe where I stop and ask myself just why it is I love so many things about such a flawed character.

For years I justified my drinking as a rite of passage, or as if it was some sort of hazing ritual in order to join the fraternity of great writers. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Kerouac, any of the greats. They drank and they drank to excess. I was already a drinker in high school, but it only got worse as my beard got thicker and my fake IDs got better. Once it was more accessible, I drank until I blacked out. Every morning I’d wake up and try to write a story about my escapades with myself as the central character. The only other character with any depth was the booze I drank. Mr. Walker was featured in my first real story, and the Southern Gentleman from Tennessee was a character in my second.

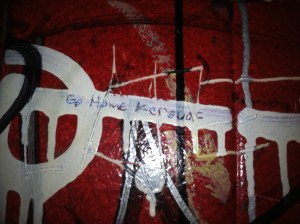

Found in a Brooklyn bar’s bathroom (an homage to the famous message written in the men’s room of the White Horse Tavern in Manhattan: “Jack Go Home!”)

This isn’t about me, though. This is about Jack’s inability to accept responsibility. He turned his daughter away, despite knowing that she was his own.

This fact, this horrible fact came to me years after I read his fiction and poetry and notes on Buddhism. As I engrossed myself in his words, I started reading biographies about the man whose work forever altered the course of my life. I found my first Ann Charters biography on a fluke, by diving into the dumpster of a closed Brooklyn Heights bookstore. She was as blinded by his figure as I, so she never mentioned his greatest sin, but as I dug deeper, I found more misdeeds.

How could my hero be so deplorable?

Kerouac married, impregnated, alienated, and abandoned his wife, Joan Haverty, and then denied paternity to a child that was unmistakably his. He dodged child support for as long as he could and even when he met his daughter, Jan Kerouac, years later, he explained that while she was a nice kid, and that she could use his name when she wrote, she was not his daughter.

Maybe he wasn’t as bad as all that. He encouraged Ginsberg to make something of himself, which led to the success of Howl, the Human Be-In, the San Francisco Renaissance, the emergence of Buddhism in the United States (thanks, Flavorwire!) …

A list of his influences on the world could go on, and if ever someone were to compile such a list it would be me. But these days, I find myself halting before I come out and say that Jack Kerouac is my favorite writer.

When I was younger and thinner, my friend, Mike, and I took a trip on our bicycles to Lowell, Massachusetts. I quit my job in order to take the week I thought I’d need to do it, and bought a tent and camping supplies in order to be prepared. We created an On the Road experience as we covered the miles between Staten Island and Lowell. We met people and made jokes that I’ll never forget. We ate lots of hot dogs and I drank lots of beer and a few manhattans. Mike went to sleep early, but I never missed an opportunity to get drunk and bleary eyed in new towns, where I would think about how Kerouac must’ve shared some of the same thoughts while he was drunk and alone, wondering about the universe and the nature of being a writer. Needless to say, the experience inspired a never-completed manuscript with the working title, On They Rode.

I had a bunch of friends that went to art school. They all thought that I was too much of a bro to be a hipster, and that counted against me. My college was full of bros that drove Mercedes and lived in Bay Ridge, but I was always too much of a hipster to fit in with the bros. My friends that were writers were always too intellectual and cared too much about theory and maintaining their position in their ivory towers to really talk to people and write stories for everyone. Everyone else got bored when I tried to talk about books or philosophy.

Kerouac mentions his sense of duality throughout his entire life. It’s present in his journals, his stories, his interviews, and his poetry. I, too, have never really felt like one person. Who am I? Do I want to be a roughneck beer guzzler, or do I want to talk about Foucault, as I wear superfluous elbow patches? There’s much more to this sense of a lack of self, but everywhere I turned as I read Kerouac, I found a mirror held before me.

As a former athlete with great potential, I quit competing to focus on reading and writing. Once my father left, I grew so close to my mother and was so spoiled by her love for me that I didn’t ever want to move out. The deeper I made it into the echelon of the literati, the more I realized that I didn’t fit in. I could wear the same blazer as someone else, but they wore it better. It was father’s, so the shoulders were worn and windstained from their summers at Martha’s Vineyard (some folks, not all of ’em). My stories seemed to be about people and things, while everyone around me seemed to write about ideas. The more I drank, the more I spoke, but the guiltier I felt in the morning.

Is this about me or Jack? Is there a difference?

“Don’t compare yourself to him,” Magie says. “You’re not a coward like him. You know what responsibility is.”

But that’s not fair. That’s not how I want to end this.

Happy Birthday, Jack. I know you want a drink, but are scared that one’s not enough and twelve’s too many. I know you want to toss the pigskin around, but are scared that some intellectual milksop might call you a Neanderthal. Either way, you’re my literary hero. Thanks for everything.